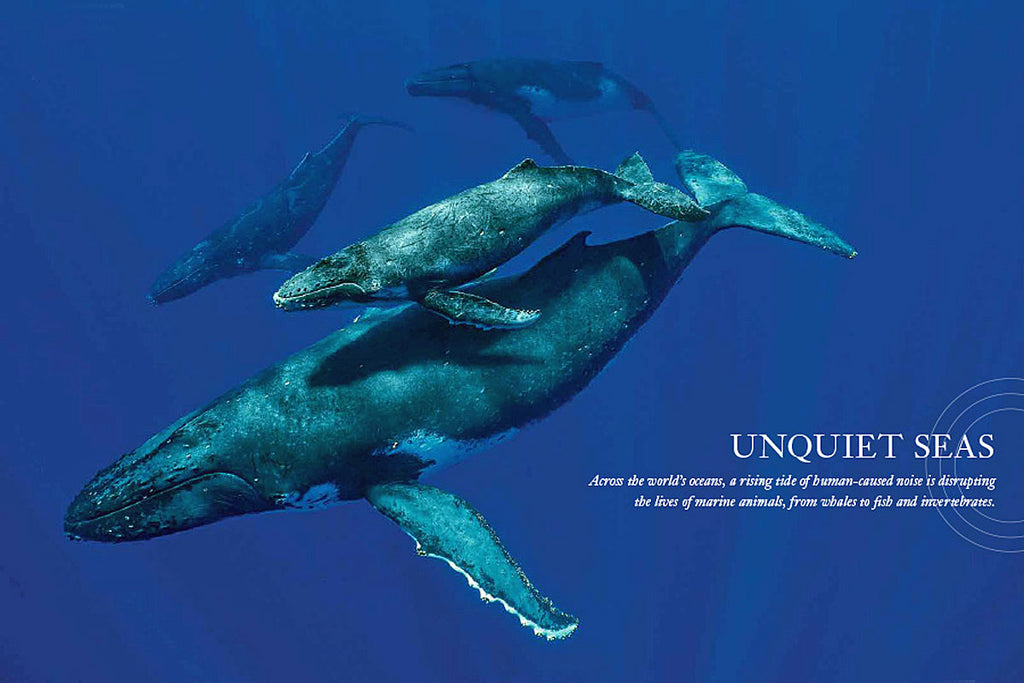

A Blue Mindset for Ocean Conservation

- News

- 31 Mar, 2020

A marine biologist champions an unconventional approach to saving the world’s waters and their inhabitants.

Laura Tangley / National Wildlife Federation

A DECADE AGO, when I first met Wallace J. Nichols on Mexico’s Baja California peninsula, the marine biologist who goes by “J” was working full time to save sea turtles. He’d estimated that at least 35,000 of the reptiles were being illegally caught and eaten in the region annually—the majority a critically endangered subspecies of green turtle known as the black turtle. The losses had caused turtle numbers to drop more than 95 percent on mainland nesting beaches.

Nichols, a research associate at the California Academy of Sciences, came up with an unconventional approach to slowing this slaughter: hiring turtle poachers to help study the animals and enforce regulations officials often ignored. Many recruits got so caught up in the effort they stopped killing turtles altogether—and the reptiles bounced back. “Last year was the best nesting season we’ve had since the 1960s,” Nichols says. “It shows that people will not destroy what they appreciate and love."

Your Brain on Water

Today Nichols is hoping a similar strategy can save the entire planet—or at least its watery parts and the creatures that inhabit them. Traditionally, he says, conservation “has relied on scaring or guilt tripping people, but that hasn’t worked.” Even putting dollar values on aquatic resources for benefits such as drinking water has failed to turn the tide against problems ranging from overfishing and pollution to ocean acidification. “We need motivators beyond fear, guilt and money,” Nichols says, suggesting instead “the emotional benefits of water.”

The key to this strategy is what Nichols calls “blue mind,” or “the meditative, relaxed state we enter when we are in, on, near or under water.” If people could understand the science behind this feeling—the processes underlying “your brain on water”—he believes it would create a potent new tool to protect our planet’s aquatic species and habitats.

Because such science does not exist, Nichols in 2011 began hosting annual Blue Mind Summits that bring together ocean researchers, neuroscientists, psychologists and others to share expertise. Last year, he published what he’s learned so far in the New York Times best-selling book Blue Mind.

While the mass movement that Nichols envisions remains a distant dream, he has seen the impact of blue mind on many individuals. Volunteering with veterans who are confronting post-traumatic stress disorder, for instance, Nichols teaches surfing and kayaking—activities that not only have helped his students “but turned them into passionate ocean conservationists.”

David Muth, director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Gulf Restoration Program, has witnessed something similar. In NWF’s work to protect the Gulf of Mexico and restore its eroding wetlands, “some of our greatest allies have been the hunters and anglers who spend their time on the water and in the marshes,” Muth says. “They are among the people who love these habitats the most.”

Laura Tangley is senior editor of National Wildlife magazine.