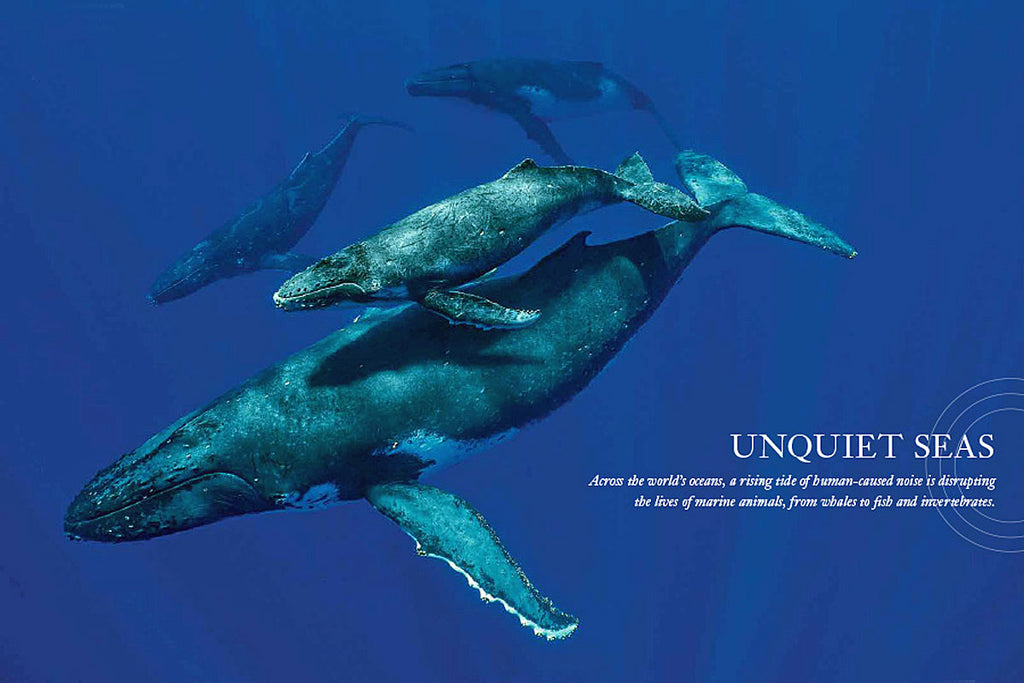

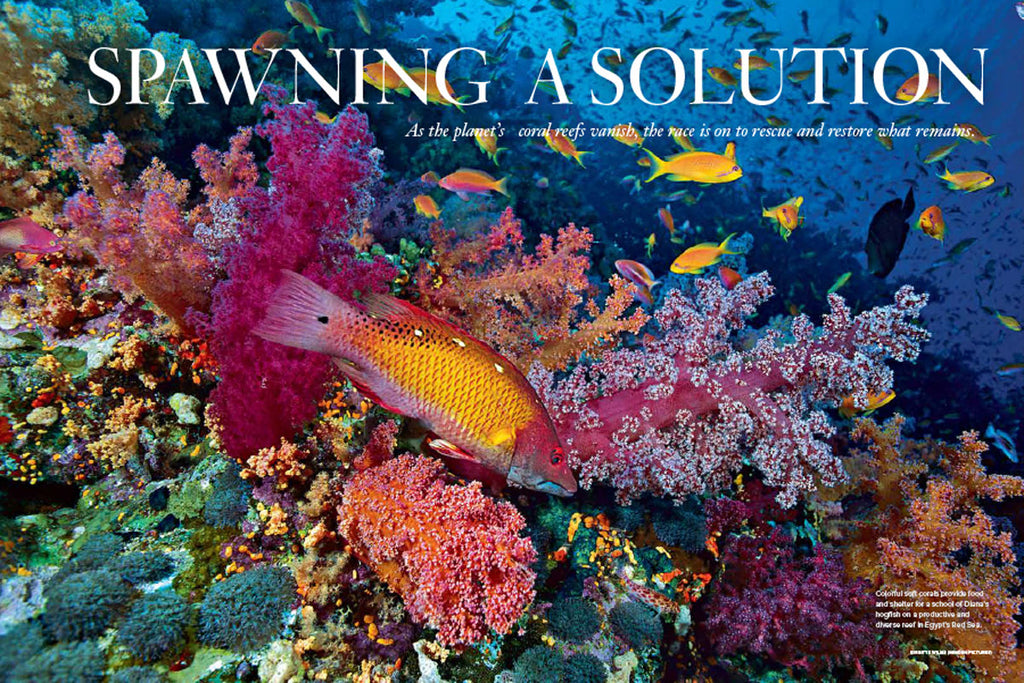

Spawning a Solution - As the planet’s coral reefs vanish, the race is on to rescue and restore what remains

- News

- 03 Jun, 2021

Colorful soft corals (above) provide food and shelter for a school of Diana’s hogfish on a productive and diverse reef in Egypt’s Red Sea. A hermit crab (below) peers out from hump coral in the Solomon Islands. (Photo above by Birgitte Wilms/Minden Pictures)

SWARMING WITH COLORFUL LIFE-FORMS that can dazzle the eyes and overwhelm the senses, the coral reefs of Palau are home to some 700 coral species and 1,400 species of fish. “You find yourself surrounded by fish of all varieties going every which way, ducking in and out of the corals in an ebb and flow of life that is incredible to watch,” says Stephen Palumbi, a marine biologist at Stanford University who has spent eight years studying and diving amidst the reefs of this Pacific island nation.

Such species richness, along with their massive structures and kaleidoscopic colors, have earned coral reefs the nickname “tropical rainforests of the sea.” Limited primarily to a band of shallow tropical and subtropical waters straddling the equator, coral reefs are found in the continental United States only off the coast of Florida, where the 360-mile-long Florida Reef Tract makes up the third largest coral barrier reef system on Earth. Some divers still recall exploring those reefs many decades ago and experiencing a sense of wonder not unlike Palumbi’s.

But that is no longer possible. Like many of the planet’s reefs, Florida’s have long been in decline due to human activities. According to Erinn Muller, coral restoration program manager for Mote Marine Laboratory, new results from long-term monitoring estimate that only about 2 percent of Florida’s total coral cover remains.

Now a mysterious waterborne illness dubbed stony coral tissue loss disease is rapidly spreading through the reefs, with nearly half of the tract’s 45 coral species susceptible. “The speed at which it travels is scary,” says National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) marine biologist Jennifer Moore. Once infected, coral colonies usually die within weeks or months, she adds.

Facing potential disaster, Moore and other federal and Florida state officials recently launched the largest coral rescue effort ever undertaken. The goal is to collect up to 4,400 specimens from vulnerable coral species so they can be stored on land to protect their genetic diversity, then propagated in tanks so their offspring can be returned to the ocean. “This has never been done before on such a large scale,” Moore says of the roughly $14 million project. Currently in its third year, the effort is highlighting the hope that advances in coral rescue, research and restoration can help ailing reefs—as well as the grim outlook for those reefs due to mounting threats.

Womb of the world’s seas

Related to jellyfish and sea anemones, reef-building corals are a natural wonder of symbiosis—part animal, part plant, part mineral. Coral polyps are tiny carnivorous animals whose bodies shelter photosynthetic algae, called zooxanthellae, that provide the polyps with energy from the sun in exchange for carbon dioxide and shelter. Polyps produce a skeleton of calcium carbonate, or limestone, to protect their soft bodies. Over time, the polyps replicate themselves through asexual reproduction, producing genetically distinct colonies that aggregate into reefs.

If the world’s seas have a womb, it is these coral reefs—the most biodiverse of all ocean ecosystems. About a quarter of marine species depend on coral reefs for food or shelter. Just as high-rise buildings and cities create more habitat for humans to live in dense populations, reefs form dynamic structures that provide niches for many life-forms. This diversity of life creates a food web where plankton and algae are consumed by mollusks and herbivorous fish, which are then eaten by successively larger fish up to sharks, barracuda and other apex predators—including humans. Beyond providing fish for human consumption, reefs protect coastal communities from storm surges and support valuable recreation and tourism industries. NOAA estimates that Florida’s reefs alone generate $4.4 billion in local sales, $2 billion in local income and 70,400 jobs, primarily through tourism and fishing.

Coral reefs in collapse

Scientists believe that today’s reef-building corals originated approximately 250 million years ago, and they have survived four mass extinctions. Absent outside forces, “they are essentially immortal,” Palumbi says. “We know of no corals that have died of old age.”

Despite their longevity, coral reefs today are collapsing. The greatest single threat: Rising ocean temperatures resulting from greenhouse gas emissions are causing a condition known as bleaching. Bleaching occurs when coral polyps eject their colorful and life-giving symbiotic algae and turn white. If warm water persists too long, the corals starve and die, leaving behind only their skeletons. While some bleached corals can recover if temperatures return to normal, others never bounce back.